Turquoise is one of the oldest known gemstones. In Egyptian graves that are 7,500 years old, pieces of jewellery and inlays with turquoise were found. The oldest documented deposits in the world are the Maghara Wadi Mines on the Sinai Peninsula. As early as 3,200 BC several thousand workers had been sent to mine turquoise anually. The mines were worked over a period of 2,000 years before they were forgotten.

No other mineral is revered in so many cultures as a protective stone, talisman and lucky charm. In Tibet, turquoise was considered a sacred stone, classified in six quality categories. The price of the best category topped even gold. It was also held in high esteem by the Moche in northern Peru and especially by the Aztecs, who called it "Calchihuitl". In their region the stone was mined in prehistoric times already. The economically most important deposits are still found in the US states of New Mexico, Nevada and Arizona.

Quality criteria

The following factors are important to determine the quality of turquoise:

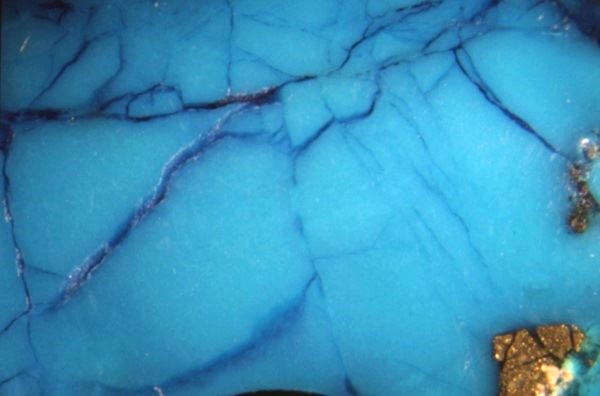

1. Color

High-quality turquoise shows a homogeneous sky blue color in daylight, sometimes with irregular, cloudy, whitish spots. In incandescent light the color of top qualities is preserved in its full beauty. Poorer qualities change their color to grayish. If the color changes completely to gray, it has to be suspected that it is not turquoise at all but odontolite (see below).

A certain content of the element copper gives turquoise its blue color. The mineral consists essentially of aluminum, copper, phosphorus and water. In addition, there is always some iron present. The mixing ratio of copper and iron is decisive for the color tone. The more iron, the greener the stone.

2. Hardness

The hardness of turquoise varies between two and six. This has two reasons:

a) Water content

Turquoise that occurs near the surface of the earth, is dryer and harder than turquoise from a depth of more than 30 meters. The latter contains more water and, therefore, is softer and more green. It is not surprising that the top qualities are found predominantly in the dry regions of our planet, e.g., in the southwest of the USA.

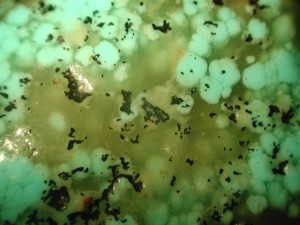

b) Quartz content

Turquoise in gemstone quality is hard and contains few pores. It has been stabilized in a natural way during and after its formation by quartz bearing water penetrating into the open pores of the stone. Therefore, the hardness and specific weight (2.5-2.8 g/cm³) are close to the one of quartz. The main supplier for these top qualities is Iran.

Poorer qualities usually have a greenish tinge and are weathered and porous. Bad qualities are very soft and can be scratched with the fingernail. They rather resemble a blackboard chalk than a turquoise and can be processed only when stabilized (see below).

Artificial Modifications (Treatment methods)

1. Paraffin waxing

Weakly colored turquoise which is dipped in colorless wax ('paraffined') acquires a more intense color and a stronger surface gloss. In addition, the surface is sealed, making the stone less sensitive to sweat and chemicals (e.g. soap). Unfortunately, this 'enhancement' does not last very long. The wax decomposes, causing the enhanced color to fade. The polish becomes dull and preexisting cracks and scratches on the surface become visible again.

2. Dyeing

Pale stones have been dyed since centuries. Even heirlooms from the Biedermeier period, when turquoise was favored in fashion, may be artificially colored. Nowadays, this treatment is usually combined with a wax or synthetic resin treatment.

3. Treatment with synthetic resins

a) Stabilizing

Very porous turquoise, which would be unsuitable for processing, is impregnated with colorless or colored synthetic resin ('stabilized'). By filling the pores with glue, even friable, brittle turquoise can be sanded and polished and gets a better color.

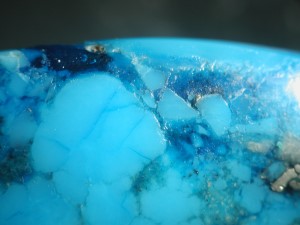

b) Reconstruction

Grinding dust and granulated waste can be reassembled ('reconstructed') using synthetic resin as a binding agent. The product is sold in rectangular bars and is usually processed into jewellery. The content of synthetic resin can be up to 40% by weight. The synthetic resin remains permanently in the stone. After an extended period of time, decomposition products (especially of the plasticizer) can change the color of the stone to a slight greenish.

4. Zachery Process

Turquoise, treated with the Zachery process

Little is known about the details of this process developed by James E. Zachery. Apparently, the microcrystalline structure of turquoise is altered in a way that the pore space is reduced. Variations in the treatment methods produce a more intense color and/or better polishability. It is said that this method only works satisfactorily if the starting material is already of medium to good quality. Chalk-like porous turquoise does not provide convincing results. According to insiders in the USA several tons of high-quality turquoise are 'optimized' in this way every year.

With the standard gemmological tests this treatment cannot be identified unambiguously. However, a trace element analysis can reveal the treatment: the potassium content of the treated turquoise is significantly increased.

Author: Dipl.-Min. B. Bruder

© INSTITUT FÜR EDELSTEIN PRÜFUNG (EPI)